It’s mid April and sunlight fills the Lake Michigan-chilled air. Warm and cold struggle against one another, as an unsettled breeze cuts through budding tree branches; all faintly green, pink, and white. Those bristling branches, along with the rumbling of a train and beeping of a reversing delivery truck are the only sounds you hear. You squint into the pale blue sky to the south, standing on the same brick pavers as you did all those years ago when you squinted into the orange evening sky in the heavy June air. The people may be gone, but you feel everything now just as then. You’re outside in the auto court of Commons West at UIC. It was here that the people, campus, and neighborhood became an indelible part of your identity, as an 18 year old kid moving to Chicago… specifically Little Italy, from the far suburbs. The place has changed over the years, yet it’s a time capsule in your mind. But what has your role in that change been and what does the place mean to you?

Your earliest memories of the neighborhood are of pit stops at Mario’s and Al’s with your parents en route to or from White Sox games. Hot dogs and Italian beef combos were unwrapped and eaten on the hood of the car or the trunk in the parking lot, and Italian ice was usually reserved for post-game dessert. But, your true Little Italy introduction was in the summer of 2008, on a sweltering June weekend. Dinner with your orientation group that first evening was at De Pasada, and you still remember the sunlight streaking through the windows; it was surprising how much greenery there was on Taylor St. compared to downtown. Afterwards, the sun sat low in the sky as you stood in the Commons West auto court with other soon-to-be students. Some played games, some flirted, and some stood idly by watching at the margins. At night you sat on a concrete bench somewhere near Student Center East without another person in sight; the campus was a great expanse, crickets harmonized with the faint hum of traffic and the wind ruffled leaves of surrounding trees. Lost in a peaceful trance, you completely lost track of time, risking being out past curfew. The problem was, each building was indistinguishable from the next, the diagonal walkways running in opposite directions. Panicked, you picked a walkway, and began shuffling hurriedly into the darkness.

Later that summer, armed with 10 or so cartons of Camels, you moved into the Commons West residence hall. Those first few nights were like summer camp. Unburdened and liberated, you immediately made the the greater- Harrison and Halsted area your home. The downtown skyline, illuminated like thousands of diamonds, shone through the massive windows in the recreation center, the thick air reeking of chlorine.

Commons West is the residence hall you called home as a freshman and your second summer as an orientation leader. It, along with its adjoining residence halls Courtyard and Commons North, are an entry point for most students who live on campus. Courtyard is where you lived the first summer as an orientation leader; an even more summer camp-like way of life. But Commons West is where you made lifelong friends, and fell in and out of love. Architecture and art students were assigned the third floor, often intermingling until dawn in the common lounge. It was a curious mix, the rigor and meticulousness of architecture colliding with the unabashed extroversion of theater. Days and nights were filled with music; you had, and still have a penchant for listening to it as loudly as possible, breaking probably a dozen pairs of headphones (and likely your ear drums) in the process. When not sending waves of music at an inappropriate volume directly into your skull, you’d use a little stereo with a docking station for your Zune(!). It’s a small miracle that you made new friends so naturally, considering your shy nature. Most nights around 11 pm you and these new friends would walk to the cafeteria for “late night”, robust meals which usually consisted of chicken nuggets and Lucky Charms. Televisions adorning the walls showed an endless loop of MTV-U music videos: Sex on Fire, Grapevine Fires, Great Expectations, Poker Face, Ready to Fall, Electric Feel, Tick Tock.

You heard Darkness on the Edge of Town for the first time in a room in Courtyard. Your friend gave you the greatest live album of all time, Live at the Hammersmith Odeon 1975 and you listened to it religiously. For Emma, Forever Ago while you trudged through the snow along Harrison. Only by the Night in the Commons West auto court. Yonder is the Clock while you walked to Ralph’s Cigar shop on Taylor to buy rolling tobacco on a warm April day; you passed Tuscany, and saw Ozzie Guillen and Harold Baines eating lunch next next to the open windows. The ’59 Sound, American Hearts, Mama I’m Swollen, The Wild The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle, and a hundred others.

The UIC-Halsted Blue line station just across Harrison from Commons West was your primary mode of going anywhere “far”. The station house was a squat building featuring brick, steel, glass, and tile. It was rusting around its edges, and complimented the soot stained, rusted, mangled chain-link fence across the street. That fence was a visual barrier between you and the, just barely out of reach, downtown skyline. You remember standing in front of the entrance with fat snowflakes falling against smoldering streetlights on that overpass with your friend on your way to see The Wrestler downtown. Snow always has a way of softening the crudeness of aging infrastructure. You would often gaze at the station while you taste-tested the surrounding neighborhood; unraveling foil and grease-splotched- sandwich paper , sitting at your cramped desk with your little lamp in the corner of your 3rd floor room.

After your second year at UIC, and in between apartment leases, you triumphantly returned to Commons West for your second summer of orientation leading. You lived in a small room with one bed, tucked away in a corner on the first floor in the shadow of a giant tree. You’d sleep in your co-worker’s room on the 4th floor, then sneak back to yours like a thief at dawn. Off days were spent lounging in that 4th floor room that wasn’t yours, the sun beating through the windows above the tree tops. Room on Fire. You spent less and less time in the small room on the first floor.

Commons West was still integral even when you lived off-campus in apartment number two. Your friend was a Resident Assistant, and you’d spend nights in his room drinking cheap alcohol and listening to Florence and the Machine. It’s not spectacular in any way, but the building holds a special place in your memory, a physical manifestation of growing into adulthood, or at least becoming an independent person. It felt like Commons West, and all of the other buildings on campus, had been there forever, stuck in time. And of course, that isn’t the case; UIC, in all of its brutalist splendor, has not only not been there forever but is an active reminder, in some ways, of the destruction and reconstruction of a neighborhood.

Although some had arrived as early as the 1850s, large waves of Italians immigrated to Chicago particularly between the 1870s and 1920s. They came to Chicago for work and settled in pockets throughout the city, with the biggest clusters around the three branches of the Chicago River near their jobs. There was a large population in the Near North Side, where Cabrini Green would eventually be built, called “Little Sicily” or “Little Hell”, but ultimately the heaviest concentration was on and around Taylor Street. Here, there were immigrants from all over Italy: Calabria, Sicily, Marche, Abruzzo, Basilicata, Toscana, Lombardia, and Romagna. The introduction of the book Taylor Street: Chicago’s Little Italy describes the identity of the neighborhood in the early and mid 20th century as a place of contradictions: “By the 20th century, the community’s duality became clear—Taylor Street was both the home to Mother Cabrini and her missionaries and hospital and the stomping ground of gangsters in the Italian Mafia, including Frank Nitti.”

Little Italy was much larger before its eastern half was demolished for UIC and the Dan Ryan expressway (I-90/94). Its eastern boundary is now Morgan St., but once extended as far east as Canal St. In fact, Chicago’s first recognized pizzeria, Granato’s, was located on the southwest corner of Taylor and Peoria, on the site of what is now UIC’s Science and Engineering South building. That intersection was the setting for the acclaimed novel Knock on Any Door, which was written in 1947 by Willard Motley and later made into a movie starring Humphrey Bogart. The area on and around Taylor Street, in the early and mid 20th century was extremely crowded. Vince Romano, founder of the Taylor Street Archives, describes the neighborhood during those years:

In the evening, kids played on the streets while their parents sat on the front steps of their homes. Most buildings on my street were 3 stories high with 6 apartments. Between Halsted Street and Morgan Street were 4 pool rooms. They were legally set up as Social Athletic Clubs (S.A.C.s). The memory of playing tag on Goodrich School’s 3 story fire escapes. Goodrich School yard also served as a haven for the weekend dice games. A Chicago Police car pulled up every hour to collect their due. The annual Italian feast celebrations for our section of Taylor Street’s Little Italy “cinque petso Santa Nicolo” were held on the Sangamon Street side of Goodrich School. Hull House and Sheridan Park were the after-school institutions that helped to fill our non-school hours. During the summer, we went to Sheridan Park’s swimming pool. “Rags-a-line” was the cry of the junk man as he made his rounds through the neighborhood. He bought “rags and old iron” along with any other junk we managed to pillage from the neighborhood. The sound of rushing water filled our summer days. The sound of crackling wood in the schoolyard bonfire pierced the air of those summer nights. The Halsted Street merchants all displayed their produce in boxes on the sidewalks in front of their stores.

By the mid 20th century much of the built environment in Little Italy was deteriorating and it became an area of focus for Urban Renewal projects funded by the federal government. Before the construction of its campus, UIC conducted undergraduate programs at Navy Pier. By the time Mayor Daley (the first one) took office, the Navy Pier campus was overcrowded and students were lobbying for a permanent location. The University of Illinois Board, civic groups, and Daley agreed to move the campus.

In 1953, the Urban Community Conservation Act allowed for the creation of Community Conservation Boards, and Chicago’s was created in 1955. Under this act, “slum prevention” allowed the City of Chicago to take privately owned land through eminent domain. There was also an amendment to a 1947 act that allowed for the creation of Neighborhood Redevelopment Corporations (NRC) in places that were targeted as “conservation areas”. If 60% of the property owners in a conservation area approved, they could claim the other 40%. This was how local governments worked with the federal government to use public money to redevelop large portions of neighborhoods, often for private benefit. The City of Chicago used these policies to reclaim buildings in areas that they deemed to be “blighted”. In some cases the City would let its own property deteriorate which added to perceptions of blight in areas they targeted for redevelopment; a version of “demolition by neglect”. Likely, these policies were used to ensure a University of Illinois campus would remain as close as possible to downtown. In the 1950s an ordinance was passed by City Council designating 55 acres in the Harrison and Halsted area as “blighted”. An area that was largely working-class, and extremely diverse, including large populations of Italians, African Americans, Mexicans, and Greeks.

It would be irresponsible to pin the destruction or transformation (depending on how you choose to look at things) solely on the University of Illinois. An integral part of the story is the creation of the Eisenhower (I-290) and Dan Ryan expressways; they effectively formed an impervious border around the neighborhood, and literally paved the way for the new campus. Little Italy was cutoff from its surroundings yet simultaneously easily accessible to and from the suburbs. Incidentally, the neighborhood became its own island in many ways. “You can find Chicago Tribune articles calling the neighborhood a slum,” says Kathy Catrambone, co-author of Taylor Street: Chicago’s Little Italy. “I talked to many people who were here at the time, and they didn’t know they were living in a slum. They liked the neighborhood. And they really felt that they were forced out.” Catrambone says many of the neighborhood’s Italians moved to suburbs like Melrose Park, Elmwood Park and Addison. “A lot of them got on the Eisenhower and headed west.” In February 1961, the University Board accepted Daley’s offer of the Harrison and Halsted site. Since large swaths of the surrounding neighborhood were already declared Urban Renewal sites and were now controlled by the City, construction was easier and city land acquisition costs were defrayed. The federal government paid nearly two thirds of the bill with Urban Renewal funds under the Housing Act. Many neighbors and activists protested the destruction of hundreds of local businesses and thousands of homes in the neighborhood, with the most famous being Florence Scala.

People’s lives were changed forever, 8-10,000 displaced people were “deeply embittered”. They had lost the sights and smells they had always known—their smiling friendly neighbors and bustling 630 businesses, their Italian ice, and their fish markets. The “nice people”—those with money to make decisions—who pretended to be good but really weren’t, would never understand it!

Florence Scala

Despite many residents’ best attempts, construction on the new campus was imminent.

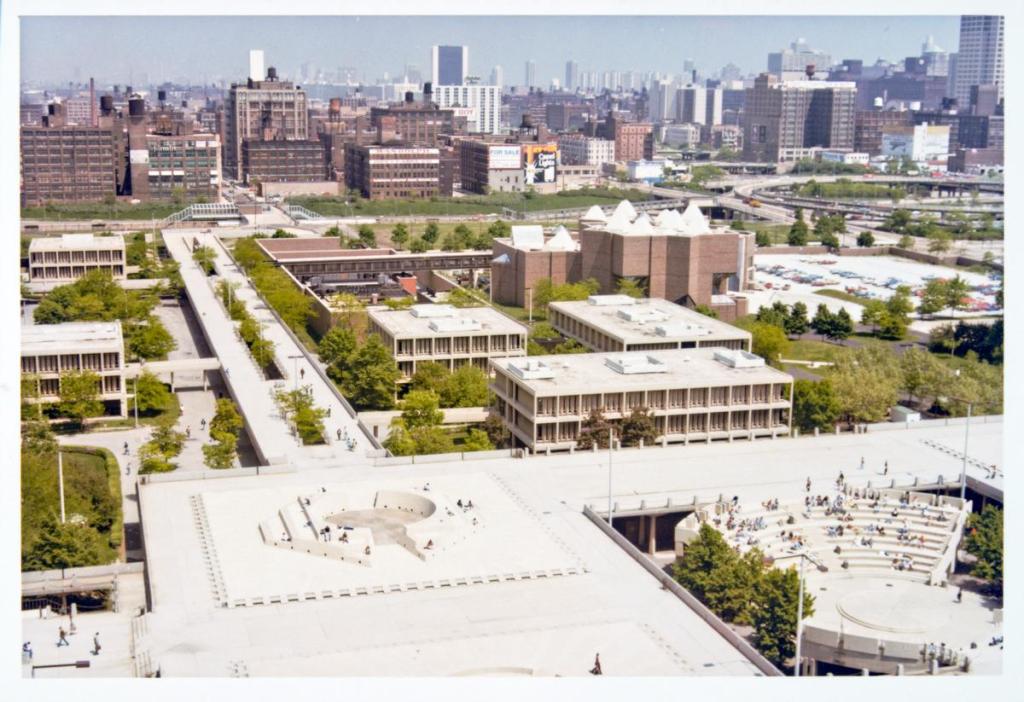

Beginning in 1963, construction of the campus and concurrent demolition of the neighborhood around Halsted and Harrison was underway. When you think of that intersection, you remember the residence halls and some shrubbery and the highway interchange but it actually once included an entire additional street: Blue Island Avenue. It was a trail that initially led to a ridge of land that people gave the name “Blue Island” because at a distance it looked like an island in the prairie. The blue color was either attributed to atmospheric scattering or to blue flowers growing on the ridge. Blue Island north of Roosevelt, which would have cut through the middle of UIC’s present-day east campus, was quickly demolished when construction started. You think back on those diagonal walkways crossing east campus and realize that you walked along the ghost of Blue Island: starting at Morgan and Taylor and ending near the corner of Halsted and Harrison; the street may be gone but its footprint is still there, hiding in plain sight.

The area around the Blue Island, Halsted, and Harrison intersection holds other significance; it was once the epicenter of Greektown. Greektown was just as important to you as the area around Taylor Street in those early days at UIC. Mr. Greek’s was bustling in those hours that existed somewhere between night and morning. Fluorescent lights, sticky tables, and guys behind the counter shouting out numbers while you and dozens of other revelers held tickets between your fingers impatiently waiting to be called; it was orderly chaos. The corner of Jackson and Halsted was full of neon signs, nighthawks, and 24 hour joints. But, the Greektown of 2008-10 was hardly representative of its former life. There were, and are, a handful of remnants of that former identity; but they continue to dwindle as gentrification and development in the West Loop increasingly expands. There was a two story building, with green and red accents that housed Costa’s Greek restaurant on the corner of Halsted and Van Buren; by 2010 it was a hole in the ground and is now a “luxury high rise with resort amenities”. Athens Liquor is now a daycare, spanning the entire first floor of that luxury high rise. Next door, the majority of the Parthenon restaurant is now nothing more than “for rent” signs. Near the intersection of Jackson and Halsted, a neon beacon still stands proudly: the sign for the Athenian Candle Company, which has been there since 1919. On the other side of the intersection sits Mr. Greek in all of its splendor. Across the street there used to be stiff competition, Greektown Gyros, which stood on the first floor of that old red brick building with its fire escapes hugging its soot-stained façade. That building was the home of the New Jackson Hotel, a low budget single room occupancy (SRO) hotel, which has since shuttered. Greektown Gyros is now a T-Mobile store and a blow dry bar, and those fire escapes have been removed, with the building’s façade lovingly restored. Zeus is still standing just west of Mr. Greek, but the Byzantium Greek restaurant next door is now a spa. Looking further north, the blue and white water tank with inscription “Greek Islands” still stands atop the 8 story brick building that houses its namesake restaurant next to the Athens restaurant. But, the relentless march of change continues, for good and bad: a dusty parking lot is now another gleaming “luxury apartment” building with a health clinic on the first floor, and across the street Santorini and Pegasus both now sit empty. Back at the Van Buren and Halsted intersection, the stone and glass façade of the National Hellenic Museum shines in the midday sun on what, again, was a dusty parking lot prior to 2011. The museum is a gateway to an area that is desperately clinging to its Greek identity, though many of those businesses have slipped through its grip.

The irony, of course, is that the Greektown you knew was already a diluted facsimile of its former self. The one-two punch of the Eisenhower expressway and UIC construction meant the once mile-long, 24-hour collection of Greek businesses and approximately 30,000 residents was now confined to a two block stretch north of its original location. It’s difficult space to be in, at once relishing the memories attached to many of UIC’s buildings and its faux-pastoral landscapes, while recognizing the devastating Urban Renewal policies that put them there in the first place. What was once a thriving urban neighborhood full of immigrants, was now a place for students to sleepwalk through monotonous days in drab brutalist buildings. It was now a place with unfinished structures with stairwells leading nowhere, buildings designed as bizarre psychological and sociological experiments, and ones completely devoid of light and personality.

Take, for example, the Behavioral Sciences Building (BSB), which is the psychological experiment of the bunch (the most deliberate one at least). The classrooms didn’t have any windows. In fact, there might not be a window in the whole place. There were always gobs of people blocking the stairs to reach the classrooms because of the central atrium’s design. It felt like a cold, cavernous maze, but with an unmistakable energy.

You turn left, towards the lecture centers, perhaps not psychological experiments, but still callous and imposing (which is appropriate, given their feature in the socioeconomic horror movie Candyman). They were large enough to get lost in a sea of people or to fit in multiple groups of new students during orientation while they were forced to watch wonderfully amateur videos welcoming them to UIC. They were also small enough for you to engage in all kinds of attention-seeking behavior as you were forced to endure attending a semiweekly psychology 101 class with your very recent-ex-girlfriend; oh, the cruel irony. At the time it wasn’t clear whether those mundane brutalist buildings provided you solace or accentuated your crumbling psychological state.

Then there are the classroom buildings, both new and old. Stevenson Hall, a relic of the campus’ brutalist roots, was old and falling apart. But, you think of unseasonably warm March days and having a writing class outside the building in the grass nearby. Grant, Douglas, and Lincoln Halls were a cluster of newly renovated classroom buildings with massive windows. You remember sun washed rooms in the spring of 2010 where you had a film and tv class that exposed you to Very Important works of art: Dexter, the Wire, Miami Vice, and the underrated movie, Quiz Show.

Those buildings, like their un-renovated counterparts, were attached by walkways on the second and third floors (a holdover of the campus’ original design that incorporated elevated walkways). In June 2008, the buildings were in the midst of being renovated. You distinctly recall standing in the unfinished third floor walkway amongst tree canopies for a group orientation activity, surrounded by green and blue.

University Hall, which is that hideous waffle-like 28 story building, can be seen from anywhere on campus, and seemed to be forever surrounded by scaffolding because of falling concrete. Legend has it, there was a family of Peregrine falcons that lived on the roof. You spent many afternoons in your French teacher’s office in that building, tracing the same steps from your apartment to her office, in a foggy trance multiple days a week. The newly released four songs on the Neva Dinova/ Bright Eyes split keeping you company: Come on show me where it is, cause I’m lookin for that happiness. You just want someone’s love to take you down. But the most important aspect of University Hall was the Chancellor’s office on the top floor. When you wanted to impress your orientation groups, you’d take them up there to overlook the downtown skyline. You always found it funny that you had to take a dingy second elevator one additional floor to emerge into a decidedly not dingy palace of burgundy wood and leather.

Further south, the library was primarily a place to cut through to get to the middle of campus from your apartment. It featured what some may consider the world’s slowest elevators. Just on the other side, the quad is a circular concrete courtyard of sorts, where there was always so much going on, it felt like sensory overload. Sometimes you were part of the chaos, other times simply a passive participant in the daily societal dance of college. You’d read (or act like you were reading), sit on the planters or benches and smoke, or just listen to music and people-watch. It was an electrifying place at times, and sometimes in the depths of frigid winter darkness, eerily quiet.

You walk to the other side of the quad and pass underneath the elevated walkways connecting Taft, Burnham, and Addams halls. These three buildings have not been renovated and are very much in keeping with the mid-1960s spirit of the campus; everything is concrete and metal, and the narrow windows ensure as little light can reach the classrooms as possible.

Along Halsted, you move past the Recreation Center and Hull House, towards Taylor St. and Halsted. While it wasn’t the only “Little Italy” in Chicago, in the early 20th century, the Halsted and Taylor St. area contained about a third of the city’s Italian population, roughly 25,000 people. For many, this area was a gateway where they first settled in the U.S. Though there was a heavy concentration of Italians in the area, it was incredibly diverse as noted on a map created by Hull House in 1895 surveying the nationalities of residents between Halsted, Polk, Jefferson, and 12th (now Roosevelt). It’s hard to believe now, but this area was considered a slum in the late 19th and early 20th century. Under the headline “Foul Ewing Street: Italian Quarter that Invites Cholera and Other Diseases,” an 1893 Tribune article describes the neighborhood:

The street is lined with irregular rows of dingy frame houses; innocent of paint and blackened and soiled by time and close contact with the children of Italy. The garbage boxes along the broken wood sidewalks are filled with ashes and rotting vegetables and are seldom emptied., Heaps of trash, rags, and old fruit are alongside the garbage boxes already overflowing. The dwelling houses and big tenement buildings that line Ewing Street are occupied by thousands of Italians. Every doorstep is well alive with children and babies dressed in rags and grime, many of their olive skinned faces showing sallow and wan beneath the covering of dirt. …Some of the dark complexioned men sit around tables through the day time hours and gamble at cards or dice with huge mugs of beer beside them.

Chicago Tribune, 1893

In response to the abusive labor practices and retched living conditions of the area’s residents, the Hull-House Settlement was created in 1889 to advocate for immigrant and workers’ rights and to foster economic, social, and creative equality. The original Hull House building was a dilapidated mansion built in 1856 by Charles Hull, and the other was built in 1905. By 1911, Hull House expanded to 13 buildings that provided places to organize, to create art and culture, build community, and reform policies. In many ways, these programs were a way to “settle” recent immigrants into their new home. Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House, is often credited as inventing the profession of social work and helping spearhead the international movement to use progressive efforts to help the poor.

Florence Scala was educated at Hull House and later volunteered there. In the early 1960s she lead protests against the destruction of the Hull House buildings for the new UIC campus. Scala ran for City Council and was a vocal critic of the Chicago political machine despite being threatened and ridiculed. She (along with another prominent Hull House supporter) even went to the Supreme Court to sue the board of Hull House for accepting the City’s settlement for the seizure of land but lost. Ultimately, the two original Hull House building’s survived and are now the Jane Addams Hull House Museum. The buildings stand in stark contrast to the hulking Student Center East building that looms behind them.

A few blocks south of the Hull House Museum are the James Stukel Towers and other residence halls on UIC’s south campus. They always felt more posh, like they were part of a different school altogether, which makes sense considering south campus is much newer than the original UIC campus. You made infrequent sojourns there, and occasionally further into Pilsen, when you found reason to break the seemingly impenetrable wall that was Roosevelt Rd. Those nights consisted of stumbling back to your dorm room from frat parties in a dingy basement on Cullerton.

When you did venture south, the lingering smell of caramelized onions and mustard would beckon you to a small Polish sausage stand, Jim’s, like a moth to flame. A festival of people would often spill out into the street. The orange lights on Union Ave. and the hum of traffic on the expressway created a strangely serene atmosphere. It was customary to eat standing up, or rather slouching, with your elbows resting on the metal counter attached to the outside of the building. The other options were sitting on the edge of the circular planters outside the entrance to the James Stukel Towers or simply the curb. It was open 24 hours a day, every day. You were there for 70 cent Polish sausages celebrating their 70th birthday. Jim’s was founded at the corner of Halsted and Maxwell in 1939 by James Stefanovic, and claims to have invented the Maxwell Street Polish sausage. Stefanovic’s son, Gus, took over after his father died in 1976, and the business continued to thrive in the middle of the Maxwell Street Market. But, like many businesses in the area, Jim’s was forced to move during the expansion of UIC. It first moved in 2001, across the street from the original location, and then in 2005 it moved around the block to its current one. A vital portion of Jim’s continued success is due to the UIC student population; the very thing that drove Jim’s and many other businesses from the Maxwell Street area in the first place. And now UIC, the owner of the building, recently forced Jim’s to close between 1 am and 6 am because of “crime”, thus damaging its all-night customer base. The irony being that the stand was originally open 24 hours for the precise reason of not getting burglarized overnight. Nowadays, Jim’s is run by Jim Koutrotsios, who started working for Jim’s in 1983 and still oversees it. The stand may be a relic of a different time and place, but it is also still undeniably a critical part of the fabric of the neighborhood – bridging the gap between past and present. You continue south, past Express Grill (a competitor to Jim’s which was also its neighbor on Maxwell Street), rows of identical residential garages, and UPS trucks parked underneath the towering highway. It’s an unremarkable site for an area that, turns out, has a remarkable history.

Maxwell Street was built around 1847, originally as a wooden plank road that ran from the south branch of the Chicago River west to Blue Island Ave. The original houses along the street were built by Irish immigrants who moved to Chicago to construct railroads and the Illinois Michigan Canal. The area around Maxwell Street continued as a gateway for people moving to Chicago from all over the world, including: Greeks, Bohemians, Russians, Germans, Italians, African Americans, and Mexicans. Starting in the 1880s, the area became predominantly populated by Jewish Eastern European immigrants, and remained that way until around the 1920s. A bustling impromptu outdoor market started in the late 1800s, and was officially sanctioned by the City of Chicago in 1912. Roosevelt marked the northern boundary of the market and 14th Street the southern, with it extending to multiple streets to the east and west of Halsted, and the intersection of Maxwell and Halsted the epicenter. It was initially an outdoor produce market, modeled after Jewish open-air markets, but would become much more diverse starting in the 1920s.

In the the early and mid 20th century, the market offered immigrants, poor people, and people of color the rare opportunity to shop freely and comfortably. Sometimes referred to as the “Ellis Island of the Midwest,” it was a unique environment where people of all backgrounds and ethnicities mingled. Of course there was another incredibly important aspect to the Maxwell Street Market: the Chicago Blues, which was popularized by artists like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. Blues became an integral part of the Maxwell Street Market experience, with shop owners encouraging the musicians and even providing them electrical power for their equipment. Maxwell Street was also the home of Vienna Beef, which first debuted at Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, was founded by Austrian-Hungarian immigrants Emil Reichel and Samual Ladany. They opened their first shop at 1215 S. Halsted, where they’d remain until 1970, making their famous sausages. Maxwell Street became the largest open-air market in the US, taking up roughly nine square blocks. It was a brilliant free-for-all with purveyors selling everything from clothing to car parts to socks and fresh vegetables. The aging UIC historian that would speak at every UIC orientation would repeat the same joke every day, “on Maxwell Street you could buy back hubcaps on Sunday that were stolen from you on Thursday”, the bit was always a big hit with the oncoming students, and there definitely seemed to be a bit of truth to it.

The street itself began to shrink in 1926, when the south branch of the Chicago River was straightened and new railroad tracks were built along its west bank. In 1957 the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway cut Maxwell Street in two and forced the market west of Union Ave. Then, after the Barbara Jean Wright Court Apartments were built and UIC began expanding south of Roosevelt, the street essentially disappeared, except for a block on either side of Halsted.

Today, as you walk to Maxwell Street, the market is long gone, replaced with brick pavers, restaurants, bars, UIC offices, and a parking garage. Statues that seem frozen in time dot the sidewalk, mourning the loss of what once was: a lady holding a bag of groceries on a bench, a man hawking produce, a stack of crates, and, of course, a blues musician. The building facades give an impression of what the area looked like in the past. In fact, most of the them were preserved when UIC razed four blocks of buildings to create University Village. Many are over a century old, and some significantly older, for example the façade at 731 W. Maxwell is from an Italianate building completed in 1876. In the years following the construction of UIC’s east campus, many of the buildings in the Maxwell Street area were deteriorating. The university was granted “eminent domain” powers by the State of Illinois to develop blocks of land along Halsted, south of Roosevelt. Buildings were razed as a result and the area was designated “blighted” by the City, which would lead to it eventually being almost entirely redeveloped to the point where its identity would completely disappear in the name of “urban renewal”.

UIC initially wanted to demolish every storefront from the old Maxwell Street Market area. But, a small group of activists banded together and created the Maxwell Street Historic Preservation Coalition (now named the Maxwell Street Foundation). Although they couldn’t keep the Sunday market in its original location (it was first relocated to Canal and now exists as a much smaller market on Desplaines in an area now dominated by industrial low-rise buildings and parking lots), they did convince the City to persuade UIC to save some of the buildings and facades. Preservation advocates initially wanted to save 40 buildings, but UIC claimed that everything west of Halsted needed to be razed. The coalition proposed a compromise which included moving 10 to 15 historic buildings from the west side of Halsted to the east, where they would be placed in vacant lots to restore the streetscape. That didn’t work either, and eventually UIC came back with a final offer: they would keep and restore a grand total of eight buildings along the east side of Halsted, and facades from 13 to-be-demolished buildings would be relocated to new commercial buildings along Maxwell.

So, as you walk along Maxwell east of Halsted, the historic character of the built environment is a slight illusion. You feel the history of the place because of the old facades, but it’s slightly disingenuous. Can a place remain authentic when most of it has been gutted and demolished with only aesthetics remaining? All those years ago you were oblivious; you’d order breakfast sandwiches from Caribou Coffee (now a Starbucks), browse for books at Barbara’s (no longer there), and eat massive sandwiches at Lucky’s (now Phlavz Bar & Grille) and think nothing of it. Perhaps, the great irony is that none of those businesses even exist there ten years later; the total erasure of 100 years of unique authentic urban culture in service of creating University Village, a sanitized version of urban life, has led to nice condos and struggling retail.

South of Maxwell, the sidewalks always seemed newer, the townhouses impeccably-kept. The wrought iron fencing and faux vintage street lamps landed somewhere between upscale suburb and historic college town. The rusted and graffiti-riddled viaduct at 16th loudly broke the illusion of insularity, and was a gate to another world (Pilsen). You turn right and walk west along 15th, tracing the shadows of tall brick buildings checkered with balconies and more wrought iron fencing. There are yellow and white daffodils and multi-colored tulips peppering perfectly manicured grass. You turn west and come upon white, industrial looking buildings also with dozens of balconies. More flowers and more iron fencing. You reach Morgan and come face to face with the faded “University Village” mural that features historical neighborhood figures in orange and pink tones against a bright blue backdrop. It was painted on a dilapidated concrete embankment, with one side having fallen apart at some point. Further along Morgan, there are a peculiar set of white, terra cotta clad buildings emerging from behind a wall of trees. They’re distinct from the other townhouses and brick residential buildings in University Village.

Turns out, these buildings, now named “University Commons” were once the home to the South Water Market. South Water was the city’s wholesale produce market originally located on the Chicago River’s main branch. In an effort to continue to beautify downtown, the market was relocated in 1925 to the area between 14th Place just south of Maxwell Street and the 16th St. Baltimore and Ohio Chicago Terminal rail embankment. It became one of the busiest produce markets in the country, with eight square blocks of buildings, 166 wholesale stalls, and commission houses. The market warehoused and distributed daily produce and food products to neighborhood markets, restaurants, and residents. It also distributed perishable commodities to markets in cities throughout the Great Lakes region. By the mid 20th century, the market began a slow decline but remained operating until 2001. A few years later, the buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Heading back north and then west along Roosevelt, St. Ignatius College Prep and the adjacent Church of the Holy Family preside over the south side of the neighborhood. The gothic revival church (1860) and the second empire-style college prep building (1870) were both built prior to the Great Chicago Fire. You’re reminded of when you and your friend snuck into the campus athletic fields late one night, the Hogwarts-like college prep building casting an enormous shadow over the artificial turf. Further west, you pass a mixture of vacant lots, parking lots, and mid-2000s architecture; mostly three story apartments and townhomes. These newer buildings replaced some of the land that was left vacant after the demolition of the Jane Addams Homes; and now this part of the neighborhood is like a smile with missing teeth. The Jane Addams Homes were a part of the larger ABLA Homes public housing project, which consisted of three other housing projects nearby. These buildings comprised the first public housing project in Chicago, and were designed by John A. Holabird, Jr., who was the lead architect for some of Chicago’s most important skyscrapers. Built in 1938, the Jane Addams Homes consisted of over 1,000 units spread across 32 low-rise apartment buildings and 52 rowhouses. Most of the first residents were Italian and Jewish families from the surrounding neighborhood. At its inception, in order to “maintain the existing racial composition of the neighborhood”, the complex was segregated and African Americans were allowed to live in only 3% of units in a particular area.

The segregation of the ABLA Homes didn’t last long, because in a short span of time (as has proven to be the case with public housing in the U.S. in general) its residents had become majority black. The neighborhood’s demographics at this time were changing, for example in 1940, US Census tract 429 (bounded by Polk on the north, Loomis on the west, Roosevelt on the south, and Racine on the east) was 96% white and 3 % black, by 1960 it was 43% white and 57% black. On July 12, 1966, the intersection of Roosevelt and Throop (which is within Census tract 429) became infamous. Kids from the nearby ABLA homes were playing in open fire hydrants to cool off from the summer heat, because their buildings didn’t have air conditioning and they weren’t welcome at nearby neighborhood pools. After police shutoff the hydrants and arrested someone who reopened them, a crowd grew and a conflict broke out with the police. This event helped spark three days of intense civil unrest on the West Side made even more nationally visible because Martin Luther King Jr. had briefly moved to Chicago at that time to protest housing segregation. Now, you stand on the corner of Roosevelt and Throop, the public housing buildings long gone, replaced with condos and townhouses on two sides of the intersection and vacant lots on other two. Redevelopment has been slow, but likely the area will be further transformed in the coming years. You count three fire hydrants.

Further west, you walk near Ashland, a dividing line between “east” and “west” campus, or rather Little Italy and the Illinois Medical District, a wholly foreign place to you aside from a few weeks spent there for Orientation training in 2009 and 2010. Back then, you’d breathe in the May dusk air alone near the side door of the residence hall you were staying at, in your own little world while the rest of your colleagues were socializing somewhere. Little Italy at one time had actually extended almost as far west as Western, and there are still a couple of holdover businesses further west on Taylor, Ferrara Bakery and Damenzo’s Pizza. Conte Di Savoia had a second outpost in the area that has since closed. This part of the neighborhood was also once home to West Side Park, where the Chicago Cubs (originally known as the White Stockings- yes, confusing) played. The first iteration of the park was located just west of UIC’s Student Services Building (where you worked at the Student Development Services office and at the Admissions office) at Congress, Loomis, Harrison, and Throop. The second iteration of the park was located between Taylor, Wood, Polk and Lincoln (now Wolcott), and is where the White Sox beat the Cubs in the 1906 World Series. It’s also the park where the Cubs had last won a World Series until 2016.

Near the intersection of Ashland and Taylor, you pass Pompei, which is one of the oldest remaining businesses in the neighborhood, it was established in 1909 by Luigi and Carmella Davino. Originally named after its proximity to Our Lady of Pompeii Church, it’s still run by the same family. Walking a few blocks north, you reach your first apartment building at Laflin and Lexington; it stands monumentally over the very end of the street creating a canyon effect. Your father had met a guy named Terry at a bar in Bridgeport before a White Sox game in 2009 and apparently he had an apartment available. You two discussed this over Italian beefs while sitting on the picnic tables outside of Al’s on an impossibly beautiful day. At the beginning of August that year, you moved in with your best friends on the third floor of an ornate greystone built in 1885. You loved how there was an inscription of the year built in the stone near the front door; it felt distinguished even if it was just an old building on a street full of old buildings. The stairs up to the third floor were narrow and craggy; old creaking wood, musty air, and dingy yellow light. There was a small parking lot directly next door allowing sunlight to pour through the south-facing kitchen windows. You were nearly kicked out for a house party the very first night of living there, people broke onto the roof from which beer cans and cigarette butts were strewn onto the sidewalk below; college students have got to be the worst tenants. There’s now a building where the parking lot was, presumably darkening the once-bright kitchen.

Little details from your un-air conditioned third floor apartment create a mosaic in your mind. Piles of cigarette butts in a yellow souvenir ashtray from the Smokey Mountains. Living room furniture consisting of a futon and some camping chairs. Your best friend leaving the coffee maker unattended while coffee grounds exploded all over the cabinets and stove, you two crying laughing from the ridiculousness of it all. You’d listen to your friend DJ for the UIC radio station high above the neighborhood in the spring with the windows open; he dedicated a song to you, “If I were the Priest”, a rare Bruce Springsteen song recorded on solely piano before his first official album came out. That same spring, you discovered the National, the opening piano riff of Fake Empire bouncing off the plaster walls, Matt Berninger’s cool baritone echoing down the hall; you get mistaken for strangers by your own friends. Your friend taught you to put a little cinnamon in your coffee, which you’d drink copious amounts of while standing on the cold linoleum kitchen floor; the smell of cinnamon wafting throughout the entire apartment. You’d sit on the counter and eat Italian subs from Conte Di Savoia, which was just a couple blocks away on Taylor Street, in that sun soaked kitchen. Conte Di Savoia has been selling imported Italian groceries and making some of the best Italian subs in the city since 1948. There was also that two-hot dog deal at Patio, a hot dog joint that’s also been on Taylor St. since 1948. You and your friend would scrounge up whatever change you had to pay for it; he’d always put too much ketchup on his fries. On warm summer nights, the extended family that owned your building and it’s sibling next door, along with some of their friends, would sit on plastic chairs on the sidewalk with a radio on. When you and your friend would walk south on Laflin to Taylor the garlic and seafood smell of Rosebud emanated from the sewage grates below. You two found a milk crate in the alley behind it once and used it to keep vinyl records in. Leaves in the nearby trees were peppered red from little light bulbs in their branches and the Rosebud sign just outside its door. Legend has it, the bar in the restaurant is made of rose-colored marble salvaged from the restroom partitions of an old Maxwell Street department store.

Life at 708 S. Laflin was largely a nocturnal one. In the winter, the living room furnace would constantly stop working and you’d often sleep with a knitted hat on. Walking along the cold wood floor and lighting the gas pilot with a long stick in the dead hours before dawn was an unfortunately common occurrence. That year you began wearing a leather jacket that you got at a thrift store, complete with a Bruce Springsteen pin circa Born to Run and a ridiculous knitted winter hat that flopped to the side just like the one he wore during the Hammersmith Odeon 1975 live concert film. You purchased a faux-antique map of the world at Blick Art Materials and pinned it to your wall, inspired by a Conor Oberst-led Monsters of Folk song. There’s a map of the world on the wall in your room. Green pins where you wanna go. White pins where you’ve been, there isn’t even ten. And you’re already feeling old. Sometimes the pace of life slowed: snow falling at night against orange street lights as you spun records overlooking the neighborhood to the east, with University Hall in the distance, and the Willis (née Sears) Tower dwarfing everything around it, dark and asleep.

When you’d walk west along Harrison back from campus, you used a “secret” gate to enter onto Laflin; it felt like a secret, anyway. You never really considered that the north side of the street at one point looked completely different, not always so open and green. In fact, this northern edge of the neighborhood felt at times like the end of the world, the highway a chasm between your reality and whatever lay beyond. Of course it hadn’t always been that way; as we know Urban Renewal, including the construction of the Eisenhower expressway and UIC, splintered the neighborhood completely and now it really is the northern end of Little Italy. Now, the Illinois Medical District is pushing east, a new Rush outpatient center is replacing the Center Court Gardens apartments that sat setback from Harrison just north of Laflin. Before UIC was built, those apartments weren’t there either. The ever-changing life cycle of a singular block in the city; from Italianate walk up buildings densely hugging the street, to scattered red-brick low rise apartments that swam in a sea of parking lots and greenery, to a massive outpatient center for a hospital. Time marches on and the built environment continually changes.

Instead of taking Harrison home from campus, sometimes you’d walk west along Lexington past Arrigo Park. The smell of garlic, onions, and marinara sauce dancing from open windows in frame cottages and brick two and three flats. You’d turn a corner and, BAM, the smell would hit you in the face, especially on Sundays. You’d walk past the place with the wood door, benches, and column painted in Italian flag colors on Racine and Lexington. The shades were usually covering the windows but sometimes you’d try to peak in them, convinced it was some sort of mob hangout. It definitely was an Italian American social club of sorts, some of which still exist in the neighborhood. And apparently it’s now the home of the Chicago School of Grappling.

One night you got lost wandering home from a party on Racine and Flournoy, in an exquisitely detailed brick and terra cotta building built in 1868, three years before the Great Chicago Fire. You always thought it was weirdly exposing, the way that the wooden back stairs and porches led to a grassy and fenceless backyard that opened up to the sidewalk and street. But in the back of that beautiful old brick building with the bay windows, the grassy expanse opened up to a world of iridescent street lights and fountains, blocks and blocks of old brick buildings that were indistinguishable in the cover of night.

You now walk south on the western edge of Arrigo Park and pass the Columbus statue. Your mind wanders to nights when your friends would jump in and swim around the fountain, splashing around like little kids; the statue disapprovingly watching over the revelry. Now, it looks unbothered in the spring sun.

You turn right and trace Arrigo’s northern edge, passing those stately rowhouses that sit in the shadow of the The Shrine of Our Lady of Pompeii. Sometimes, you’d ride your bicycle from Carpenter and Polk to your friend’s place on Lexington, passing the trees around Arrigo Park and those rowhouses, their lights flickering in grey twilight. You had reoccurring dreams of living in one of them someday; you see the multi-colored Christmas lights adorning the stoops, and the crunch of ice and snow beneath your feet. Since its founding in 1911, Our Lady of Pompeii has been a cornerstone of Little Italy’s history. Its current building was built in 1923 and was designed in the Roman Revival style, with stained glass and arches, where sacraments and mass are offered throughout the year. It’s the oldest continuous Italian-American church in Chicago.

Many Italian immigrants in Chicago were first clustered around the Guardian Angel Church, which was founded in 1899 located at what would now be Desplaines and Arthington, but was displaced by the Dan Ryan Expressway. In the first decade of the 20th century the Italian population swelled and started to move west of Hasted and eventually the Italian population west of Morgan was split into a different parish and Our Lady of Pompeii was built to serve them. In the 1920s and 30s the Italian population between the Chicago River, Van Buren, Paulina, and Roosevelt contained “Perhaps half of the Italian population of the city”. A few blocks north sits another gorgeous church, Notre Dame de Chicago. The parish was founded in 1864 by French-speaking immigrants. The current building replaced the first one at another location, and was completed in 1892 in the Romanesque Revival style with a heavy French influence. It’s one of the few French landmarks remaining in Chicago and was added to the National Register for Historic Places in 1979.

You head south back to Taylor Street. There’s a modern-ish looking building that you remember as the National American Sports Hall of Fame, which honored Italian-American Athletes from a wide variety of professional and olympic sports. The hall had more than 200 Italian-Americans honored as inductees including Vince Lombardi, Rocky Marciano, Tommy Lasorda, and Mario Andretti. The museum has since closed when the building was sold in 2019. It will soon reopen as a Neighborhood Hotel (which is a local group of boutique hotels).

Across the street, Plaza DiMaggio (sans the DiMaggio statue, he packed up and left with the Hall of Fame) is the punctuation point at the southern end of Bishop Street, with its blocks of houses uniformly set back from the street with fenceless front lawns. A brick building circa 1886 frames the plaza on the east and was home to a barbershop which has since been replaced by a bakery, and now Kong Dog – which slings Korean hot dogs. You head south from Plaza DiMaggio and reach the Taylor and Loomis intersection. Davanti Enoteca and Francesca’s on Taylor both sat prominently there and have since closed. Devanti since replaced by a new upscale-ish Italian restaurant Peanut Park Trattori, Francesca’s replaced by Adda Indian Cuisine. Further, you pass Sweet Maple Cafe, which has incredible biscuits and one of the best breakfasts in the city; your go to is the porkchop topped with caramelized onions, eggs, and breakfast potatoes. Laurene Hynson opened the cafe on Taylor Street in 1999.

Next to Sweet Maple sits Scafuri Bakery, which has been on the street since 1904. Luigi and Carmella Scafuri opened the bakery after immigrating to Chicago in 1901 from Calabria, Italy. After Luigi passed away in 1955, his daughter Annette Mategrano continued the family’s legacy until closing the bakery not long before you arrived at UIC. After a few years of renovations, Annette’s great-niece Michelle reopened Scafuri in May 2013. You remember the bare windows through which you could see the dust-covered barren interior; other times the windows would be decorated with airbrushed “seasons greetings” and fake snow, left unkempt for months to fade, sunlight covering the facade from the vacant lot next door (now a condo building). After a few years, a handwritten note on plain white page emerged, teasing the bakery’s imminent return, “coming soon” “since 1904”. Longing for some unattainable and more authentic Little Italy in your mind, those simple words tantalized you.

Across the street from Scafuri, you walk along a pristine stretch of sidewalk, completely level and absent anything that would dare sully its perfect face. You remember nights walking the cracked and crooked sidewalk here next to nothing but overgrown weeds, gravel, broken glass, and the occasional wrapper. This stretch of the street showed the open wounds from the unkept promises of Urban Renewal. But now, towering above the new pristine sidewalk is an innovative mixed use building: part library and part affordable housing. The new Little Italy branch of the Chicago Public Library system has replaced the Roosevelt Branch, which was that ordinary looking library you often passed further east on Taylor. You wonder if this shimmering new complex elicits the same hopeful feelings that the Jane Addams Homes once did when they initially opened. Or perhaps this new approach to community, education, and affordable housing merely belies the same issues that eventually led to the downfall of public housing. Only time will tell.

In 1999 Mayor Richard M. Daley announced the “Plan for Transformation”, a massive proposal to demolish most of the existing public housing in Chicago and redevelop the land. The Jane Addams Homes were demolished by 2007, except for one building just east of where the new library stands. This four story brick building at 1322-24 West Taylor St. opened in 1938 as the first federal government housing project in Chicago. It housed hundreds of families over six decades and has been vacant since 2002. You’d walk past it often, tantalized by its weathered mystery. It was saved through relentless organizing of public housing residents, who insisted on saving it to create the National Public Housing Museum (NPHM). The museum will celebrate their stories and become a site of resistance against misrepresentations of people living in poverty. The museum broke ground in 2022 and should open in 2023.

Walking east past a mix of more vacant lots and mid-2000s two and three story buildings, you reach the intersection of Taylor and Racine. Gentile’s Wine Shop is still there on the corner, so is the Papa John’s that moved into a spot that was vacant the first couple of years you were in the neighborhood. The storefront next to the Papa John’s has seen a rotating cast of frozen yogurt/ice cream shops over the last decade, and is now a Japanese ice cream shop called Kurimu. Next to it was once a vacant lot, and is now a Japanese bakery called Mochinut. The red faded awning of China Night Cafe still hangs prominently across the street; you were a frequent consumer of their lunch special, your shoes sticking and unsticking from their floor with each step.

After another block you reach a place that’s been a staple of your life since the early 90s, Al’s Italian Beef. It was founded in 1938 by Al Ferrari and his sister and brother-in-law, Frances, and Chris Pacelli, Sr. The (debated) legend goes that the recipe for Italian beef was developed in Al’s kitchen during the time of the Great Depression out of necessity. The family sold their sandwiches at a food stand on Laflin and Harrison, and delivered them to local businesses until opening the location on Taylor St.

You then reach Nea Agora packing company, which you and your friends always imagined was some sort of front for something (it’s not- it’s a butcher/ meatpacking company that’s been in the neighborhood for decades). But, this also means you’ve reached Carpenter St., where just a few blocks north at Polk St. stands your second apartment building.

You turn left on Carpenter and pass an all-too-familiar alley, the one behind Galileo school’s massive red brick building by the Sheridan Park baseball fields. You always seemed to generally have a good rapport with people from the neighborhood, nonetheless, the relationship between students and the old guard seemed to be at once beneficial and occasionally contentious. There was an issue in that alley once: a beer was thrown, threats were made, but it didn’t amount to much. This escalation occurred basically because you and your friend decided to galivant down the alley, dressed in suits to feel like a part of the Little Italys you knew from movies. Anther issue arose on Carpenter a few months later, some words were said, voices were raised, and later on that night you heard a baseball bat tapping at your first-floor front window. Somehow that situation blew over as well. Aside from a few squabbles here and there, though, it was a relatively symbiotic relationship. Particularly between the most entrepreneurial of the bunch; the supply and demand for various forms of recreation are quite high in the vicinity of Carpenter St.

These few blocks around Carpenter and Polk were well-worn territory, you’d take walks by yourself nearly every evening, still destroying your ear drums in the process. The walks pivotally provided you a sense of ballast. You felt like the main character in Anyone’s Ghost by the National. You pictured yourself in Blue Jeans & White T Shirts by the Gaslight Anthem –We’re never going home until the sun says we’re finished, and I’ll love you forever if I ever love at all, with wild hearts, blue jeans, and white t shirts; lyrics from that song are tattooed on your arm. You aspired to the defiance of Bamboo Bones by Against Me! –Don’t let them break you, don’t let them tell you who you are. In the summer hundreds of lightning bugs would emerge when the sun would retreat behind the trees on the west side of Sheridan Park and the sky would fleetingly turn cotton candy pink. That park is where you found heartbreak and desperation on the bleachers, where you’d eat frozen yogurt with a girl, and where you’d play whiffle ball while fireworks erupted from the alley.

Although it felt like home, there was still a relatively frequent nagging voice in the back of your head that would insist you were an imposter in this neighborhood. It wasn’t yours, it was theirs; you were merely a visitor or worse an accomplice to its active destruction by various government entities and institutions of higher learning. You could feel it in subtle ways, but the majority of the time you paid no mind. Your friends would sit on the fire escape outside their third floor apartment just like generations of people probably did before them; it was a brick building built in 1889 tucked away on Aberdeen by a fountain. The rear of it was part of an assortment of buildings, the wooden porches connected by walkways like catacombs. They were probably tenements in a past life, a still-standing representation of Chicago’s old vernacular architecture. And now they were places where you’d build lifelong bonds with people, where you’d feel waves of joy and waves of regret, full of palpable longing – sleeping on your friend’s couch even though your apartment was just a block away. They were now part of a new vernacular.

On the other side of that fountain is Tufano’s Vernon Park Tap, which was founded in 1930 and is still run by the same family. Current owner Joey DiBuono is the grandson of the founders, Joseph DiBuono and wife Teresa Tufano. It stands proudly along Vernon Park along with its compatriots (a pair of 135 year old worker’s cottages) defying UIC’s east campus, University Hall leering down on them. Vernon Park, between the campus and Racine was a sort of living museum of the old neighborhood. One day an elderly lady emerged from one of those slouching frame houses that have since been demolished. She squinted into the midday sunlight on the wooden porch that led to the second floor front door, and sincerely asked you (and your girlfriend at the time) what day it was. She must have lived in that house before the university tore down the neighborhood directly across the street for a massive parking lot. That house, with its kelly green awnings, and the one next to it have become vacant lots at some point in the intervening years, leaving just those other two houses standing directly next to Tufano’s remaining.

In that first spring and summer at UIC, you and your new friend from Common’s West hitched a plan to live together before the new school year started. You’d walk around the streets, looking at front windows of the old brick and terra cotta buildings living under tree canopies just west of campus in search of “for rent” signs. If you were lucky, they’d have a website, but usually it was just a piece of paper or cardboard with a handwritten phone number, typically in permanent marker and sometimes barely legible. Now, you walk west along Vernon Park and picture yourself and your friend sitting on a curb, the sun fading in a cloud of nicotine; you were buzzing like cicadas at the prospect of your very own place to live. Back to Polk, you pass more rows of houses built in the 1870s and 1880s and then reach your second apartment building.

Hours of your life were spent on the sidewalk, usually chain-smoking, in front of the building directly outside your first floor apartment. Watching pigeons play in puddles, and inspired by the Tom Waits classic Nighthawks at the Diner, you wrote some sort of jazzy spoken word thing for English class called The Pigeon Prince of Carpenter Street. Sometimes, you felt like a ghost amidst the cacophony of screaming school kids at Galileo just down the street. It was a sweltering late July day, steam rising from the streets, when you moved in. You had just finished your second straight summer as a UIC Orientation leader and were in the midst of a heady new relationship with the aforementioned co-worker who stayed on the 4th floor of Commons West. After moving all of your belongings into the back room next to the kitchen (most of them piled into black garbage bags in lieu of boxes), you and your roommates spent hours on a couch you found in the alley, which would eventually be moved inside and made a permanent fixture of the living room. You held royal court on that couch in a sea of fellow students, strangers, and friends. The neighborhood was alive. As with your first apartment, this one was a monument to chaos, perhaps even ramped up to another level; the scent of cheap tequila and tobacco floating through the air. Polk and Carpenter was always bustling with people hanging out at Carm’s and Fontano’s; UIC students and longtime residents alike. Sitting at the sticky white tables near the bathroom in Fontano’s, there’d usually be someone playing guitar plugged into a tiny amp directly across from you. Standing at the front counter at Carm’s, where the sweet old matriarch of the place once gave you food even though you had no money, Steve would shout wisecracks; a real “ball buster” as they say.

Every night when the street was still and quiet, orange street lights and yellow haze from the dangling Carm’s sign would peer through your living room blinds casting shadows across your face. Film Noir. Just like 708 S. Laflin, your bedroom window had nothing but a brick wall view, so you’d spend most of your time in that living room under the cover of that Carm’s sign. Fontano’s and Carm’s seem like they’ve stood opposite each other at that intersection since the beginning of time. After fighting in World War I, Aniello and Gilda Fontano opened Carm’s grocery store that would later turn into the two businesses across the street from one another. When Carm’s first opened, it sold Italian groceries and Italian ice (your roommates always preferred Carm’s while you preferred Mario’s). In the 1960s, it started serving hot dogs, Italian beefs, and subs. Around the same time, Fontano’s opened across the street, taking over the grocery aspect of the business and selling incredible subs. Both businesses are still run by second and third generations of the Fontano family.

You head back south along Carpenter and reach its end point, where you found yourself dozens of times: Little Joe’s, which has been in business since 1946. It was often a raucous, messy affair. The bar was basically a time capsule; all wood, dark tones, and neon signs. The stools were properly wobbly, and some of them duct taped to keep from falling apart. Little Joe (Assenato) himself would grace the place with his presence most nights. Near little Joe’s was Ralph’s, where you’d buy rolling tobacco (Drum, in the dark blue package) and occasionally smoke cigars inside with boisterous old timers. They’d sit on the leather couches and watch the small television while surrounded by a cloud of smoke. Ralph’s moved, thankfully just a little west towards Racine where Rosal’s Italian restaurant was located. Nearby, you remember the back “lounge” at Sinbad’s hookah bar (now an I Dream of Falafel, arguably an upgrade), the little televisions playing an array of music videos while UIC students inhaled a variety of fruit-flavored tobacco.

Vivid colors and scents, and fragments of interactions with people make up the neighborhood in your memory. You made fleeting and lifelong friendships; forever fossilized in a time and place. It’s an intriguing dichotomy, you love a place but realize part of it was demolished and people were pushed out for the very reason you were there in the first place, but the old and new parts equally contribute to your fondness of it. Can you love Little Italy and UIC at the same time, even though UIC was responsible for much of the demise of the original neighborhood? Would the neighborhood have changed over time regardless? When Tuscany on Taylor opened in 1990, there were about 20 classic Italian restaurants on Taylor St., now there’s less than five. But, the neighborhood is still hanging on to some sense of anachronism.

You wrote this 13 years ago, and it still rings true:

Little Italy still lurks in the shadows on and in the surrounding areas of Taylor Street. It resides in the decrepit empty rooms of the abandoned housing project. It lives behind the counter of Conte Di Savoia and its plethora of Italian meats and groceries. It is inside the smoke-filled comfort of Ralph’s Cigar Shop. It lingers in the alley behind Al’s Italian Beef.

Now, it still lives on the corner of Polk and Carpenter with Carm’s and Fontano’s, in that apartment building across the street, and that old church on the corner that always had construction work being done. It lingers on Lexington and Laflin, and with the folks who sit on their plastic chairs on the sidewalk on warm summer nights. It permeates through the ball fields in Sheridan Park, and the fountain that greets you in Arrigo Park. It floats around in the sweet smells of Scafuri Bakery. It hides amongst the bottles of wine and groceries at Conte Di Savoia. It can still be found at Pompei and Rosebud. And every summer when the Little Italy Festa takes over the street for a weekend in August.

Perhaps you were there walking its streets every day for the end of an era of sorts. A transitional time that, now well over a decade later, has seen the neighborhood shed its skin even further. In many ways, the Little Italy of the past is merely an echo. The Hall of Fame has closed, Joltin’ Joe has vacated his throne at the end of Bishop Street. Rosal’s closed. The club on the corner of Lexington and Racine is no more, its Italian flag colored columns and benches outside now painted over. The pizza slices and cannolis at Taylor Made Pizza are no more. Now, new development has taken hold throughout the neighborhood. Finally, some parts of that toothless smile that is the Roosevelt Square are being filled in and the built environment is destined be drastically different in the near future.

But definitions change, and the place contains billions of memories from millions of people. Yours are just a small part of it, little vignettes that still float in and out of your periphery, like dust particles in sunlight. They’re shadows from the brick buildings and ancient trees elongated across the sidewalks and pavement in the setting summer sun. Even as people move on and move out, new cohorts of students replenish the neighborhood and campus every year, a continuous circle that goes on and on. The campus grows and evolves, the neighborhood gathers millions of stories and memories, and stacks them on top of one another, year after year. They build and shape the sidewalks of the neighborhood and the walkways, grass, and concrete of the campus, they rest in the fire escapes, wooden porches, and bricks, layer upon layer.

You end your sojourn where it all began for you something like thirty years ago: Mario’s. Mario’s Italian Lemonade was founded in 1954 by Mario DiPaolo, who came to Chicago from the Abruzzo region of Italy. Mario opened a general store at Harrison and Leavitt, where he met his wife, and they then opened a new store at 1066 W. Taylor St. In the early 50s, Mario gave his son “Skip” a hand-crank lemonade machine to channel his rambunctious energy by making and selling lemonade on Taylor St. in front of the store. Back then, a horse-drawn wagon delivered ice in hundred-pound blocks, and lemon juice was squeezed by hand before churning. After a few years, Mario, Skip, and their family members scrounged for wood through the neighborhood’s alleys and built the lemonade stand. According to DiPaolo, there were probably 15-20 frozen lemonade stands in Little Italy at the time. People could obtain a hand cranked machine for a couple hundred dollars at Charugi Hardware. Skip never left the neighborhood, and still runs the stand with his wife Maria, and their three kids. Now, white boards cover the stand’s windows with the words “Closed for the season. Reopen May 1st” scribbled over them in green and red ink. Maybe nobody is simply just from a place. Maybe people are made up of places, as we in turn, make them along the way. You turn to leave knowing that you’ll be back again, standing on this sidewalk in the summer with dozens of others. All those people and the neighborhood itself, building one another’s identity, memory by memory.